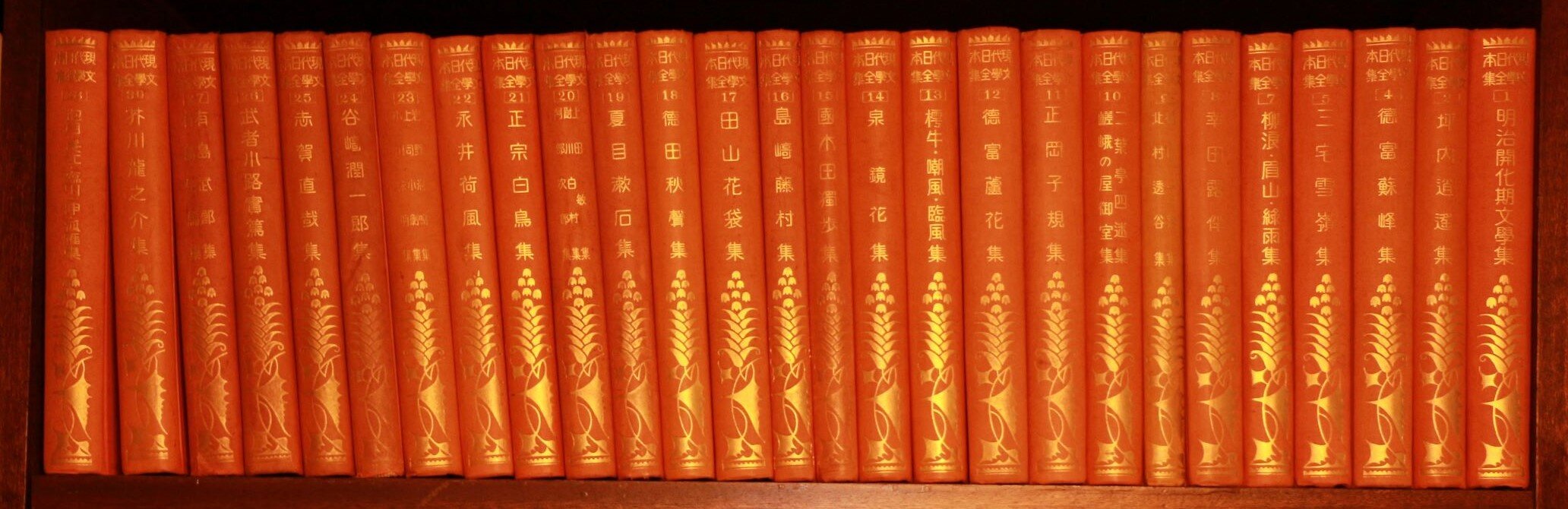

日本語で日本近代文学を書く小説家 A novelist writing modern Japanese literature in the Japanese language

Fan, Jiayang. “Filial Devotion, Sorely Tested in Minae Mizumura’s Novel.” Review of Inheritance from Mother. New York Times, June 9, 2017.

Appraisal of Minae Mizumura’s Writing

“From the beginning, she suggests, modern Japanese fiction was born out of an engagement with English literature—an engagement that her own work continues. Even readers who have no particular interest in that literary history will find in Mizumura a fascinating example of how a writer can be at the same time imaginatively cosmopolitan and linguistically rooted.” —Kirsch, Adam. “Resisting English.” New York Review of Books, vol. 66, no. 16, October 24, 2019.

“. . . Mizumura’s novel, like much of the rest of her work, . . . insistently resists translation or its possibility. . . . Minae Mizumura’s literary career and texts have offered an almost Kafka-like resistance to translation, in both their form and content. . . . Mizumura . . . left Japan when she was a teenager and moved with her family to Long Island where she spent two decades, going to high school, doing undergraduate and graduate work at Yale University, and ultimately teaching Japanese literature at Princeton. But she has written poignantly of her constant retreat throughout this period into the written Japanese word and specifically into the great works of Japanese fiction that she read obsessively from the time she left Japan. In 1990, she returned to her native country with the express intention of becoming a literary figure—an ambition she has more than realized. Mizumura is bilingual and in many ways bicultural, and yet she is . . . devoted to Japanese literary tradition . . . For Mizumura, what this has meant is the creation of a body of work that in various and creative ways resists attempts at translation and cooptation by the globalized positionality she had thrust upon her at an early age. Each of her works, for different reasons, is, in effect, untranslatable on one or more levels—not overtly or explicitly but philosophically and contextually.” —Stephen Snyder. “The Murakami Effect. On the Homogenizing Dangers of Easily Translated Literature.” Lit Hub, January 4, 2017. New England Review, vol. 37, no. 4, 2016.

Appraisal of An I-Novel

“In an age of so many books about identity, “An I-Novel” stands out for the tough questions it poses. It’s not difficult to read, since Mizumura is a fluent and entertaining writer. . . . Mizumura’s books reclaim the particularity, the untranslatability, of her own language. And they do so without the slightest whiff of nationalism. . . . What’s difficult about her work is the questions it raises. How to be national without being chauvinistic? How to be local without being provincial? How to use identity as the beginning of the discussion rather than — as it is so often today — the final word? In Mizumura’s works, the question is always open.” —Benjamin Moser, New York Times

“It has been gratifying, moving even, to read a work by a writer of such maturity and sensitivity. Mizumura creates memorable characters who have real depth. Juliet Carpenter’s translation conveys the novel’s qualities with graceful power. I can’t remember the last time

I enjoyed—and marveled at—a novel so richly insightful and a translation so elegant and readable.” —Van C. Gessel, translator of Endō Shūsaku“A genre-defying meditation on emigration, language, and race. . . . As she alternates between the mundanities of her day—what to eat, when to make a phone call—and more philosophical reflections on racism, xenophobia, and linguistic alienation, Mizumura’s narrator (and her author) produces a brilliant document that seems, if anything, more relevant today than upon its original publication. . . . Mizumura’s work is deeply insightful and painstaking but never precious.” —Kirkus, starred review

“At its heart, An I-Novel is a deep meditation on the writer’s internal life, on straddling cultures and wanting to be at once authentic and original. Exploding the conventions of a long-established literary form, Minae Mizumura’s novel is a landmark in contemporary Japanese literature, finally brought to English-language readers by Juliet Winters Carpenter’s titanic feat of translation.” —Tash Aw, author of We, the Survivors

“In Minae Mizumura’s autobiographical novel, multiple languages and literatures mediate an expatriate girlhood’s dislocations of nationality, race, class, and gender. In the process, the work upends the assumptions of the I-novel, a genre thought to provide unmediated access to its male, Japanese author. The resulting observations are unsparing, sharply ironic and often very funny.” —Ken Itō, author of An Age of Melodrama: Family, Gender, and Social Hierarchy in the Turn-of-the-Century Japanese Novel

An I-Novel by Minae Mizumura is an immigrant story turned on its head. . . This is a novel about language and literature, and how language can feel like home. . . certainly among the most important translations from Japanese this year. It is a tour de force by translator Juliet Winters Carpenter of one of Japan’s most exciting writers. —Leanne Martin, Chicago Review of Books.

“A thoughtful meditation on belonging, language, and identity politics, An I-Novel is a must-read.” —Reading under the Olive Tree

“An I-Novel is an intriguing, nuanced portrait of a family in flux, and of a young woman finding her creative center between two worlds.” —Meg Nola, Foreword Reviews

Appraisal of The Fall of Language in the Age of English

“[A] highly charged book.” —Eric Banks, The Chronicle Of Higher Education

“Rigorous and wide-ranging . . . . This book is a cracker.” —Peter Gordon, Asian Review of Books

“An eye-opening call to consciousness about the role of language.” —Publishers Weekly Tip Sheet

“the best book I’ve ever read on translation and multilingualism” —Benjamin Moser, New York Times Book Review

“The Fall of Language in the Age of English deserves wider coverage (and debate).” —Flavorwire

“Mizumura has crafted a book that stimulates thought, excites passions, and encourages debate. For these alone, it is well worth a read.” —Erik R. Lofgren, World Literature Today

“Translators Juliet Winter Carpenter and Mari Yoshihara have done a superb job of rendering [the text] into clear, readable English.” —Japanese Studies

“The care with which Mizumura has crafted this book . . . [makes] the reading of it a pleasure, allowing for wit and personality to shine.” —Full Stop

“[Mizumura's] book is a 'text to read' in the 'universal library,' to use her terms.” —Selma K. Sonntag, Journal of Asian Studies

“A stirring call to consciousness about the role of language . . . . For English speakers, the book presents an important opportunity to walk in someone else's shoes.” —Publishers Weekly

“Persuasive, elegantly written . . . . [The Fall of Language in the Age of English] is highly deserving of attention, from English and Japanese speakers alike, as well as from anyone concerned about literature's past and future.” —Rebecca Hussey, The Quarterly Conversation

“This powerful, insightful work analyzes the predicament of world languages and literatures in an age when English has become the universal language of science and the default language of the internet . . . . Rich, profound meditation on language and literature.” —Claremont Review of Books

“A call to arms for everyone: for all non-native English speakers to embrace and champion literature in their own languages, and for English speakers to be that little less arrogant in their use of their mother tongue, which just happens to have become the world's universal language.” —Sophie Knight, The Japan Times

“Mizumura traces how the myth of the 'national language,' a pure upwelling of political character, coincided with the flowering of the nation-state—and, even more fascinatingly, of the novel itself . . . . 'Language' may be in the book's title, but Mizumura has really crafted a conservationist's plea for literature.” —Katy Waldman, Slate

“There is incredibly smart stuff in here . . . Mizumura's ability to weave together so many strands of history (lingual, academic, economic, geopolitical) paints a clear picture of the evolution of Japanese literature, with commentary on the rest of the globe being a pleasant byproduct.” —Graham Oliver, The Rumpus

“In The Fall Of Language in the Age of English, Minae Mizumura shows, better than anyone ever has, how English is wrecking other languages — reducing even great literary languages, including Japanese and French, to local dialects — and makes a vigorous case for the superiority of the written over the spoken word.” —Benjamin Moser, New York Times Book Review

“The Fall of Language in the Age of English is—or at least can be—valuable to any literature-interested reader. Certainly, it is an interesting personal introduction to aspects of Japanese writing, and its transitions across recent centuries, as Japan's own position internationally has shifted.” —M. A. Orthofer, The Complete Review

“A dazzling rumination on the decline of local languages, most particularly Japanese, in a world overshadowed by English. Moving effortlessly between theory and personal reflection, Minae Mizumura's lament—linguistic and social in equal measure—is broadly informed, closely reasoned, and—in a manner that recalls her beloved Jane Austen—at once earnest and full of mischief.” —John Nathan, translator of Light and Dark: A Novel by Natsume Sōseki

“The Fall of Language in the Age of English provocatively participates in current debates on world literature, translation, reading, and writing in the age of global English and the Internet, bringing forward a new and illuminating perspective on the translingual formation of national languages and the now endangered arc of modern literature. It is written from the viewpoint of a noted Japanese novelist as well as from a wider theoretical and historical perspective.” —Tomi Suzuki, Columbia University

“In the late 19th century, Japan followed the trajectory of many European countries in building a strong modern nation-state centered on the identity of its national language, but, as Mizumura points out, that national language did not directly emerge out of the vernacular. Japanese was not, like modern European languages, a written version of the local, spoken language. Instead, the national language of modern Japan depended on a long tradition of writing that mixed logograms and phonograms, a complex notational system that resulted in a rich literary tradition in which writing did not correspond directly with speech. As a written language, Japanese developed what Mizumura calls a “mesmerizing polyphony,” a complex notation system that combines logographic and phonographic use of characters from Chinese with two different sets of native syllabary (kana).” —Haruo Shirane, Public Books

Appraisal of A True Novel

“Riveting.” —Page Views, New York Daily News

“Absolutely fantastic.” —Azure Scratchings

“an ambitious social critique.” —Times Literary Supplement

“Minae Mizumura's massive “A True Novel”—boldly appropriated post-Modernist revisioning of "Wuthering Heights"—coolly reportorial voice.”—Joyce Carol Oates

“This powerful and lengthy story by the winner of Japan’s prestigious Yomiuri Literature Prize is sure to make a profound impression.” —Sunflower and Moth

“This is a masterly cross-cultural adaptation of “Wuthering Heights,” set in Long Island and postwar Japan.” —IhsanTaylor, “Paperback Row,” New York Times, Jan. 9, 2015.

“A smart, literate reimagining of Wuthering Heights . . . Mizumura’s book is an elegant construction, fully creating and inhabiting its fictional—its truly fictional—world.” —Kirkus

“[A] fascinating example of a cross-cultural adaptation . . . A True Novel suggests that it isn’t only writers who are influenced by timeless novels but also the forces of history itself.” —Wall Street Journal

“Ambitious . . . [A True Novel raises] questions about where the line between fiction and remembrance lies.” —Los Angeles Times

“Mizumura meets her literary challenge with impressive sophistication and irresistible emotional power.” —Booklist (Starred Review)

“Imaginatively sets Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights in postwar Japan… the narrative is colloquial, loose-limbed, and finely detailed; it’s anything but a slavish imitation of the original.” —Library Journal

“A mind-bending saga…[A True Novel] encompasses generations and continents, and Mizumura’s unfussy prose draws clear pictures of various shifting cultural patterns and behaviors.” —Bookpage

“[Deftly translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter…[A True Novel] is also an ambitious social critique.” —Times Literary Supplement

“Readers happy to lose themselves in a narrative but who prefer to lose themselves in a maze that is cunningly wrought, that is artful enough to stand with a book rightly called a classic, will relish “A True Novel.” —The Japan Times

“A True Novel is one of the finest novels to come out of Japan in recent years.” —The Modern Novel Blog

“Through the night, as wind and rain pummel the house, Minae enters a different reality. This is the enchantment of narrative: the exchange of one world for another, light bulbs for ghost fires. This is the promise of every novel, and Mizumura’s keeps it.” —Music & Literature

“A True Novel is a masterpiece that breaks down all kinds of barriers, one that deserves to transcend the borders between languages and nations as well.” —The Rumpus

“Minae Mizumura is, to put it simply, what was missing in Japanese literature: A real woman, a real writer who writes real novels.” —Página/12 (Argentina)

“I won’t say a word towards Mizumura’s extravagant masterpiece, the better to tempt you to seek it yourself.” —Ben Ladouceur, “Behind Every Story, A Less Interesting Story,” Open Book, January 30, 2018.

“A passionate reimagining of the romantic classic Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë that takes place within the Japanese community in the United States during World War II and the decades immediately following.” —La Nación (Argentina)

“The book was so exciting that I couldn't wait to turn the pages; I read it almost at one sitting . . . . A True Novel comes alive by its intricate structure and thereby stands out among hundreds of other typically boring contemporary novels.” —Toshiko Hirata, poet, Yomiuri Shinbun, November 3, 2002, p.12.

“A True Novel is a story within a story within another story. It revolves around one mysterious man with a tragic history…For the first time in ages I found a book that keeps me awake at night.” —Booklust

“A True Novel soars, with unique anxieties about the intersection between Western ideas and Japanese ideals. [Mizumura’s] protagonists…are characters with psychological depth that make the lengthy 850 pages worth the time. Whether you’re interested in a story about young love or a mid-20th century Japan setting, A True Novel delivers.” —Mochi Magazine

“Stories within stories, Minae Mizumura’s A True Novel is like a set of matryoshka dolls, with the gem-like truth at its interior. Reading it, we find great moments of history intertwined with the elegance and vulnerability of the heart’s simplest and most urgent desires.” —Lucy Ferriss, author of The Lost

“With A True Novel, Mizumura delivers a haunting, poetic novel of a young Japanese girl who dances on the precipice between becoming American and remaining Japanese as she also narrates the mysterious tale of an angry Japanese man who conquers and is conquered by the America they both come to know.” —Antoinette van Heugten, best-selling author of Saving Max

“A riveting tale of doomed lovers set against the backdrop of postwar Japan . . . . Mizumura’s ambitious literary and cultural preoccupations do not overwhelm the sheer force of her narrative or the beauty of her writing (in an evocative translation by Juliet Winters Carpenter) . . . True Novel makes tangible the pain and the legacy of loss . . . . Its] psychological acuteness, fully realized characters and historical sweep push it out of the realm of pastiche and into something far more alluring and memorable.” —New York Times Book Review

“Concentric narratives connect and transform into a critical appraisal of commercial expansion and cultural decline . . . notable are Minae’s edgy insights into class distinctions, trans-Pacific cultures, and modernization’s spiritual void. A transparent translation and the author’s stylistic clarity smooth navigation between storylines. Photographs create the sense of browsing through an album—a nearly 900-page album encompassing two continents and several decades.” —Publishers Weekly (Starred Review)

“The pleasures of A True Novel exceed those of the conventional storytelling kind. Mizamura is an author profoundly concerned with literary tradition and she pulls off several feats here, merging a shishōsetsu work (first-person Japanese autobiographical narrative) into a honkaku shōsetsu (panoramic Western novel), while successfully recasting Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights in a postwar Japanese setting. Its effect recalls the greatest of Yasujiro Ozu’s films or Chekhov’s shorter fiction: a deep humanism is palpable beneath the dispassionate narrative.” —Three Percent

“[T]here is no doubt that the story each narrator tells could be a stunning piece of craftsmanship on its own…Juliet Winters’s skilled translation enables the language to flow naturally, presenting no barriers to this exciting journey into the heart of the Japanese culture, which is important because the novel is not only a devastating love story, but also a reflection of history and society through the lives of each narrator.” —Verse

“This is a book for readers who yearn for the juice and substance of nineteenth-century novels, for the drugged wonder of immersion in another world, in other souls. A True Novel not only satisfies that yearning but is a commentary on the phenomenon—and, further, a cool accounting of a traditional society’s material gains and cultural losses in the transformations of the last century. Of contemporary writers, only the likes of Ian McEwan or Jane Smiley have achieved this combination of scope and emotional power.” —Anna Shapiro, author of Living on Air

“Minae Mizumura’s exemplary epic A True Novel is a rapturous homage to this innocent era of literature’s birth. All the tropes of a nineteenth-century British novel are at work here and sing in harmony with a different kind of story, one of mid-twentieth century Japan. A True Novel is equal parts contemporary Japanese family drama and a Victorian English Classic, and together they create a deeply rewarding and nuanced reading experience.” —About.com

“After reading this long book, full of precise tableaux of Japanese people and landscapes, one is struck with a deep sense of grief toward Japan, which has neglected its own history. There is no other way to describe the publication of A True Novel except to say, it marks a decisive moment in the history of Japanese literature.” —Natsuo Sekigawa, Asahi Shinbun

“Honkaku shosetsu (A True Novel) by Minae Mizumura, its serialization just completed in the literary journal Shincho, is a perfect classic from its very inception. Spellbinding and nostalgic, the novel resonates with orchestral majesty, even to its smallest details. A True Novel is born true to the legacy of modern literature . . . . The story is simply fascinating, no reservations, no conditions attached . . . . Describing with great veracity the rapidly changing Japanese society over the course of half a century, A True Novel has the power to surpass many of the original works of great literature on which it is based . . . . Vividly portrayed in the novel is how a nation's history puts its people at its mercy. Yet what actually emerges even more than the force of history is the snowfall of months and years that befalls each of us equally, the private moments of time that eventually disperse and disappear as time flows on.” —Mariko Ozaki, lliterary critic, Yomiuri Shinbun (newspaper with the largest circulation in Japan), December 25, 2001, p.13.

“What is a “true novel”? It is difficult to come up with a good definition, but whatever it is, if what is presented as such did not give readers the impression that it is indeed a “true novel,” it would be quite an embarrassment for the author. I must say I was rather apprehensive before reading it, though it was not my problem. Yet when I got through with the book, I was quite impressed. This truly is a “true novel.” Put simply, the novel is the contemporary Japanese version of Wuthering Heights, and it is amazingly well executed . . . . It evokes not only Wuthering Heights, but also other works of literature like The Great Gatsby. It is filled with allusions to the classics of literature, both from the East and the West . . . and her writing style that calls them to mind is just astounding.” —Masashi Miura, critic, Yomiuri Shinbun, October 22, 2002, p.15.

“This book is truly fascinating to read. I even remained awake the entire night, . . . drawn to the complex web of human dramas described in the novel. I could not but be amazed by how brilliantly the author invokes the subtle interactions among the characters . . . . Mizumura's skill as a novelist is impressive, endowing a mysterious atmosphere to the country houses of Karuizawa and heightening the reader’s imagination . . . .” —Masayuki Yamauchi, professor, University of Tokyo, Mainichi Shinbun (a major newspaper in Japan), October 27, 2002, p. 10.

“What we have here is a novel that is dream-like yet real, depicting a world that is too good to be true, yet truthful. After reading this long book, full of precise tableaux of Japanese people and landscapes, one is struck with a deep sense of grief toward Japan which has neglected its own history. There is no other way to describe the publication of A True Novel except to say, it marks a decisive moment in the history of Japanese literature.” —Natsuo Sekigawa, critic and novelist, Asahi Shimbun (the most respected newspaper in Japan), October 30, 2002, p. 7.

“Portrayed in the novel is romantic love that is painfully passionate and miraculously pure. We regain in reading this novel what we have almost forgotten: the excitement, sorrow, and heartache we once felt reading love stories . . . . A Man and a woman from "different backgrounds" fall into forbidden love. The earnestness and seriousness of the two lovers create a magnificent realm all their own.... Moreover, this novel portrays with a remarkable accuracy what lies behind their romantic love—postwar Japan's social transformation from poverty to prosperity . . . . It succeeds in becoming a nostalgic family saga... by describing the lives of not only the two protagonists but also those around them—especially the lives of the pre-war middle class, which have now disappeared . . . . A sense of wonder struck me as I finished reading the novel.” —Saburo Kawamoto, critic, Shukan Asahi (a major weekly newsmagazine published by Asahi Shimbun), November 29, 2002, p. 125.

“How great it was to read A True Novel! Whatever Mizumura writes, whether novels or essays, you always feel her honest love of and simple passion for literature. Her writing always strikes me with power that only truth can deliver. Honesty, love, passion, truth—I look for other words, but to no avail. She is a writer in whom those almost forgotten words still breathe life. She writes sparingly yet she is a novelist in the center court of literature . . . . How many times did I get into fights with my family and deprive myself of sleep for the sake of this book? I even cried out loud at several places. The book portrays with radical force not merely the sadness of love but, more importantly, the very sadness of human existence. And what great density of time is packed into the work . . . . This book allows the reader to feel with an almost physical poignancy how the fates of private individuals are engulfed by the current of history.” —Masayo Koike, poet, Tosho Shinbun (a weekly book review), November 30, 2002.

“A True Novel by Minae Mizumura is not only the best novel of 2002, it is the most recommended companion for your year's end and new year's. Its narrative structure is elaborate but the novel is easy to read and enthralling. Both worldly and Parnassian at the same time, it is endowed with the power to satiate a sophisticated reader. The dialogues are effervescent and entertaining, and all of our five senses are fully engaged in reading this richly rendered chronicle, full of reminiscence and remorse.” —Kazuya Fukuda, Shukan Shincho (a major weekly newsmagazine), December 12, 2002, p.126.

“I just finished reading Minae Mizumura's A True Novel and I can't get it out of my mind. Who would have ever thought that Heathcliff and Catherine would be re-incarnated in contemporary Japan and would come down the escalator at a new theatre complex in Tokyo, so affectionate with each other? And how audacious of the author to begin the story with what was missing in the original, that is, the success story of Heathcliff, or rather, Taro Azuma? What is most stunning in this novel, along with the dazzling skill of its narration, is the author's critical will against the current state of affairs and her desire to resist Japan's turn toward frivolity and vapidity. This novel is wildly exhilarating.” —Kan Nozaki, professor, University of Tokyo, Ronza (a monthly journal of criticism published by Asahi Shimbun), January, 2003, p.314.

“Kawamoto: This was a productive year with a number of long novels; I thought the best one was A True Novel by Minae Mizumura. There were other well written novels, but A True Novel was the most rewarding to read. Each and every character in it is solidly drawn. Miura: Mizumura demonstrated how she was unafraid not only to confront Wuthering Heights face to face, but also to remake it entirely anew and entirely her own.... If you study the details, she has also made subtle use of The Cherry Orchard, The Great Gatsby and the like, yet she doesn't make you notice it. Anyway, the plot is so fascinating that you are done reading before you know it. Kawamoto: You sense in A True Novel not only the general gaiety typical of the high economic growth period ... but also the lingering effects of war. Taro Azuma is a repatriated child from China. There has never been a novel that looks from a child's point of view at the trauma left by war and poverty. The way A True Novel depicts that trauma was most moving and brought tears to my eyes.” —Saburo Kawamoto and Masashi Miura, critics in a recorded dialogue, Bungakkai (a monthly journal of literature and criticism), January, 2003, p. 128-150.

Appraisal of Inheritance From Mother

“A must-read novel about the tangled bonds of motherhood…gorgeous and intimate.” —Washington Post

“[A] compelling exploration of family history and its impact on relationships and traditions.” —Publishers Weekly

“A fascinating example of the overlap of Japanese and foreign influences, nicely brought to the fore by Mizumura.” —Complete Review

“A story whose distinct layers, like lacquer, are laid over one another to form a lustrous whole. In Inheritance from Mother, the lines between past and present blur; the East is transposed like a palimpsest over West; and life shades into literature.” —The New Republic

“A thoughtful examination of the emotional complexities and contradictions that surround the aging and death of a parent. Through deft, engrossing storytelling, Mizumura addresses the reality of this all too commonplace experience. It’s a timely, substantial novel and a pleasure to read.” —Structo

“Mizumura has taken all the classic themes of the grand newspaper novel—sibling rivalries, unhappy marriages, family inheritances—and woven them into a moving tale for our own day.” —Michael K. Bourdaghs, Professor of Modern Japanese Literature, University of Chicago

“[a] gorgeous and intimate novel . . . One of the most entrancing things about this novel is that it retains the rhythm of a serial even in bound-book form . . . Mizumura’s writing is urgent yet thorough, and her plot — with its multiple divorces and infidelities, scheming, legends and deaths — just short of overwrought. But her prose is controlled and as dense as poetry . . . Part 2 is a wandering, sometimes frustrating sequel to the very straightforward Hemingwayesque quality of Part 1. Yet so worth it. The resolution of Inheritance From Mother is natural and satisfying in myriad ways.” —Ann Bauer, The Washington Post.

“there is admirable ambition in the way Mitsuki’s story expands into a much larger portrait of middle-class anomie in a Japan still reckoning with its past and the paradoxes — and fraught compromises — of its identity . . . In Mizumura’s novel, the new world may be constructed a thousand times, but invariably it reaches back into the old, the kind of inheritance that just may emanate darkness — as well as light.” — Jiayang Fan, The New York Times Book Review

“Mizumura’s realism embraces family dynamics and bodily decline, both of which are anatomized without a hint of sentimentality. But it is perhaps most evident in her candid treatment of money . . . Mizumura depicts the ordeals of middle age with intelligence and empathy. The very modesty of Mitsuki’s needs is demoralizing . . . The reader shares in Mizumura’s sheer pleasure in invention as she raises narrative possibilities and discards them, changes focus and atmosphere, and adds new characters to keep the momentum going” —Adam Kirsch, The New York Review of Books

“The 66 chapters are brief, emotionally combustible . . . . There are also fascinating asides about the history of the serial novel in Japan, because Mitsuki believes that these fairy-tale melodramas were responsible for shaping her mother’s acquisitive personality and may have contributed to her own marital unhappiness. So Ms. Mizumura craftily mixes the old with the new, creating a highly readable throwback to popular dime novels that replaces gilt with guilt and romance with real talk.” —Sam Sacks, The Wall Street Journal

“The plotting is brisk, with an aggressive forward momentum more characteristic of thrillers or pulpy fiction. The sixty-six chapters are economical, each detailing a single event or memory. But the fleet-footedness of her plotting matches the profundity of her investigation into family relationships ... The novel’s power, in large part due to this intelligent sequencing of events, lies in the sense that the first chapter’s point of jadedness becomes inevitable, a naturally unnatural response to a lifetime of thwarted dreams.” —Darren Huang, Full Stop

“The author demonstrates that what appears calm on the surface can hide unimaginable depths of despair. In this compelling exploration of family history and its impact on relationships and traditions, Mizumura offers insight into how Japanese culture and shows how two daughters can survive the damage wrought by an onerous parent.” —Publishers Weekly

“A novel of female endurance and obligation . . . The novel has an unblinking focus which accumulates to near-claustrophobic proportions, yet the decisions finally made by Mitsuki arrive with a persuasive sense of late-life liberation. A long, minute, subtle consideration of aging, loyalty, and the bonds of love grounded in the material details of Japanese culture but resonating far beyond.” —Kirkus

“Mizumura’s startlingly unsentimental portrait of a woman who begins to examine her own life after her mother’s death electrified readers when it was…serialized in Japan’s Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper in 2010 and 2011…Chapter by chapter, Mizumura gives her heroine courage to believe in the right to independence and happiness—an inheritance not of wealth, but of self-knowledge.” —O, The Oprah Magazine

“A deeply moving exploration of the complex and often fraught relationships between mothers and daughters. Mizumura uses her astute powers of observation to reveal, layer by layer, the turmoil and anger roiling beneath the surface of her characters. A beautifully crafted novel with universal appeal.” —Cari Luna, author of The Revolution of Every Day

“Mizumura’s previous novel in English was transcendently romantic; in Inheritance from Mother, romance manifests mainly as liability and false lure, while the years devolve from poetry to prose. The ingenious plot, however, produces vitality and beauty mercifully different from the conventional love story’s, surprising us with gleeful relish and bursts of sheerest gratification.” —Anna Shapiro, author of Living on Air

“In this coming-of-a-certain-age novel, the longings and desires of a middle-aged daughter are as bountiful as those of Emma Bovary. If Douglas Sirk and Agatha Christie went on a writing junket to Japan, they might return with this quietly seductive novel, in which Minae Mizumura’s heroine uses her mother’s inheritance to compose a new life story for herself.” —Judith Pascoe, Professor of English, University of Iowa

“For anyone with a family, Inheritance from Mother will almost certainly pierce those abstruse narratives we create of our own families, and in the best cases, recontextualize those relationships with more intricacy and compassion . . . Mizumura endows her characters with complexity in a stunningly graceful manner . . . Mizumura’s depiction of the relationship between eastern and western ideals is one of the most gripping aspects of the novel . . . Mizumura inevitably evokes comparisons to Isabelle Allende and Amy Tan for her focus on strong and resilient female characters, multi-generational families in a culture where family comes first, and dynamics of Western invasion into Eastern traditions. But her work is steeped in self-awareness, brazenly critiquing the traditional structures so integral to her history. Mizumura does not avoid diving head first into those things that leave the deepest scars: death, infidelity, and the surrendering of dreams are where she starts.” —Neda Baraghani, The Rumpus

Appraisal of Zoku meian (Light and dark continued)

“Her 1990 debut novel, Zoku meian [Light and Darkness continued], is a tour de force in which she creates a very plausible, stylistically pitch-perfect ending to Meian [Light and Darkness], the last, unfinished masterpiece by Natsume Sōseki, Japan’s most important modern novelist. It was an audacious debut for Mizumura on one level, yet on another it was a logical project for someone who had made a long study of Sōseki’s work and who, as an outsider to the Japanese literary establishment, was not abashed in the face of the great master the way a writer educated in Japan might have been. What is clear about the project, however, is that while it can be translated on the level of sentence and plot, it is a work that is, by definition, fundamentally untranslatable in the sense that it is so deeply embedded in its context and dependent for meaning on a literary and cultural knowledge of Sōseki’s original. To understand Zoku Meian, the reader must know the plot, style, textual history, reception, and role in Japanese literary history of its source text, Meian. As a fragmentary, dependent work, standing in relation to a classic text that is largely unknown outside Japan except to a handful of experts, it is, in effect, impossible to render into comprehensible English or, for that matter, any other language—which made it, to say the least, a pointed debut for a bilingual, international returnee seeking to reincorporate herself into Japanese literary life.” —Stephen Snyder. “The Murakami Effect. On the Homogenizing Dangers of Easily Translated Literature.” Lit Hub, January 4, 2017. New England Review, vol. 37, no. 4, 2016.